The Diamond Necklace Affair

Those are the stock answers, but neither marked the first act of open defiance against the crown. Americans would say the Boston Tea Party or Boston Massacre or Stamp Act riots marked that.

Frenchman may say the erosion of royal authority that overthrew France’s social order began with the Estates General in 1789, but before that the first event to both rock the foundation of monarchy and also display open defiance of royal authority was the “Diamond Necklace Affair” or the “Affair of the Queen’s Necklace”.

This article retells the story of the diamond necklace affair. This story that launched the French Revolution was one of the most notorious public scandals of history. It involved great fortunes made and lost, of avarice, mystery and intrigue, it pits great forces in French society against each other, but in the end severely damaged the monarchy to the great detriment of both, and destroyed for all time the reputation of the second highest public figure in the French monarchy. The story starts with three players; the first is that famous public figure – the Queen of France: Marie Antoinette. This story had its root cause, its currency and appeal from this most star-crossed figure of French history.

The Queen

Marie Antoinette was an Austrian Princess when she came to France, at age 15, in 1770, to marry the Crown Prince. She and husband Louis XVI were still teenagers when they ascended the throne in 1774. Unlike her shy awkward husband, Marie Antoinette was admired for her legendary beauty, grace and elegance and her tastes which set fashion trends for Europe. She took pride in her appearance and in her ancestry as a princess of Hapsburg, the oldest royal house of Europe. Her arrogance brought resentment from old nobility of France, a country which had been at war with Austria for much of the 18th century. Marie Antoinette also attracted gossip for her inability (due to Louis’s impotence) to become pregnant and produce an heir to the throne, for her youthful disregard of court etiquette, and for her frivolous and costly lifestyle. This lifestyle included gambling, masked balls, late night rendezvous and rumours of her having had numerous love affairs with both men and women. Even by 1785, an underground literature existed that reviled the Queen in pornographic songs, pictures and pamphlets.

Much of Marie’s fast and loose behaviour in her first decade in France was a reaction to her marital frustration; but in 1778, Louis had an operation and the couple at last had children. By 1785, Marie Antoinette had given birth to three children. She was maturing and her lifestyle had grown far more sedentary and less extravagant. But that change was hardly noticeable to the uninformed public and did little to assuage those who had already developed their dislike for her.

The Nobleman

Against this backdrop in 1784, enter the two key players in the story – one, a great nobleman, the other, a woman swindler who dupes him. The nobleman Louis René Édouard de Rohan was Cardinal of France and son of one of its oldest and most famous noble houses. However, Rohan had a problem. He was in disfavour at the French court. The Queen’s mother Marie Thérèse did not like Rohan, frivolous dandy, when he served as a diplomat to Austria. After her mother scorned him, Marie Antoinette refused to receive Rohan and had not even spoken to him for a number of years. For 10 years, Rohan had longed to become a member of the Queen’s close circle, with the new favours and patronage that could bring. Rohan, the dandy, was also attracted by the Queen’s beauty and fancied that if she would only admit him to her circle, he too might partake in her amorous favours, of the type frequently rumoured in court.

The Swindler

The woman swindler is the Countess de Lamotte. She was the daughter of the old and famous Valois family, but the family has long-lost its resources. She was quite impoverished when she arrived in Paris. But Lamotte was also quite attractive and brazen in her desire to escape poverty and obtain an aristocratic life of comfort and leisure. She sought to enlist the sympathy of the royal court in the fate of a woman from one of France’s old houses. She was given to fainting spells at court and in doing this has at last receives notice from Madame Elizabeth, the King’s sister who provided her with some funding. She was also noticed by Cardinal Rohan. By 1784, she had become his mistress. Even though she had not succeeded in obtaining the interest or support of the Queen or even met the Queen, Lamotte succeeded in convincing Cardinal Rohan that she has the favour of Marie Antoinette. Rohan fully subscribed to the tales in court circles of Marie Antoinette’s sexual dissipation. Using her full figure and attractive looks to great effect, Lamotte spun stories that convinced Rohan that she, Lamotte, was becoming one of the Queen’s new lesbian love interests, just as Rohan hoped to become her lover as well.

The Necklace

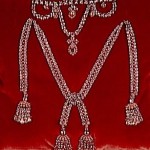

Now enters the object all seek – the necklace. The necklace was 2800 carats. First was a choker of seventeen diamonds, five to eight carats each; from that hung a three-wreathed festoon and pendants; then came the necklace proper, a double row of diamonds cumulating in an eleven-carat stone. And finally, hanging from the necklace, four knotted tassels. It cost 1,600,000 lives. Perhaps in today’s currency, this is the equivalent of $100 million. The jeweller Charles Bohmer had the beautiful necklace made for Madame du Barry. But Louis XV died, du Barry was banished from court, and Bohmer placed his hopes on the new Queen to purchase the necklace. She modelled it before her ladies, but would not purchase it or permit Louis to buy it as a gift for her. “Better to buy a new ship of the line (battleship or aircraft carrier equivalent) than to spend such a sum on a necklace, regardless of how beautiful …” she said.

The Opportunity

Boehmer too had seen Lamotte at court. Like Rohan, the jeweller too believed the Marie Antoinette rumours at court. The jeweller appreciated Lamotte’s looks, believed she had the Queen’s favour and sought her out as an intermediary. Knowing Rohan’s keen desire to obtain the Queen’s favour, Lamotte saw her opportunity to trade on the belief of both men in her intimacy with the Queen to satisfy the desires of both men and enrich herself. She told the cardinal that the Queen wanted him to secretly purchase the necklace on her behalf. The cardinal obtained the necklace from Bohmer and gave it to Mme Lamotte, expecting the Queen to pay for it. Of course, Marie Antoinette never saw the necklace. Lamotte gave the diamonds to her husband, who took them to London and sold them. Lamotte forged letters from the Queen to Rohan attesting to her interest in the necklace, approving the plan and Lamotte’s role, and indicating Rohan could expect return to the Queen’s favour

The Rendezvous

The letters satisfied Rohan for a time, but at Versailles, Marie Antoinette ignored Rohan as always. He wanted a real sign of her interest in him. Rohan needed more and it was at this moment in the gardens of the Palais Royal in Paris the final piece to her puzzle fell in place. It came in the form of a 25-year old street-walker, Madame d’Olivia. Buxom and blonde, with an arrogant strut, such that people called her “Queen”. Lamotte was at once captivated by the young d’Olivia’s striking resemblance to 29-year old Marie Antoinette. And so, Cardinal Rohan did get the sign of favour he wanted from the Queen… or so he thought. On a summer night in 1784, Lamotte outfitted the woman in a lawn dress, the same as the famous Marie Antoinette “en gaulle” painting then on exhibit. The veiled woman briefly met the Cardinal in the gardens of Versailles, late at night as Antoinette was rumoured to meet her lovers. The false Queen gave the Cardinal a rose. She said, “All may be forgiven …” and hurried away, leaving the Cardinal under the illusion that he had met Marie Antoinette.

The Confrontation

Unaware of the real drama unfolding, Marie Antoinette was busy preparing herself for the part of the saucy barmaid Rosina in the controversial play Marriage of Figaro. On the day of one her rehearsals Boehmer’s invoice for the necklace arrived and was discarded by the Queen. Later, Bohmer came to Versailles and spoke to the Queen’s servant Madame Campan, seeking payment. He displayed forged letters signed by her, and told how Rohan was involved in acquiring the necklace. At last, Marie Antoinette realized the serious of the case, and summoned Bohmer to Versailles. She was furious with Rohan, so was Louis XVI. The royal couple demanded a trial. They arranged for the arrest of the Cardinal, the highest clergyman in France, in the most public way, handing him the arrest warrant in the great hall of Versailles with hundreds present. He was brought before the King and Queen, who confronted him with the swindle and would hear none of his professions of innocence and that he too had been made the fool.

The Trial

The public arrest of the Cardinal of France had already caused a national sensation, and the acts of King and Queen that followed added new fuel to the fire of public interest and imagination. That this nobleman with whom she had not spoken a word in 15 years would dare to presume that she, Marie Antoinette, would meet him at a secret rendezvous, was a serious insult to her name and reputation. The proud Queen demanded public vindication of her good name. The matter could have been handled quietly at the court or by the Vatican. Louis’s advisors suggested caution, but the wavering King agreed to a public trial before the Parlement of Paris. France of 1785 was not used to such public events. While rumours of Marie’s errant behaviour were prevalent in the capital, they now became sensation for all of France. The charge against the Cardinal was lese-majeste, insult to the dignity of the Queen. For months, the nation was gripped by the mystery of the diamond necklace and the recounting of the Queen’s reputation that led Rohan to believe she had participated. The public was riveted by the accounts and characters, the swindler Lamotte, the prostitute who impersonated the Queen, the $100 million necklace at stake at a hard time when the country faced bankruptcy. Through it all, Lamotte held to her story that the Queen was behind it all and had the necklace.

The Verdicts

The case to defend the Queen’s dignity would never have been easy. Though she never appeared, this case put the life of Marie Antoinette was on trial. Many jurors could believe based on her past spending and loose lifestyle that Marie Antoinette was capable of these activities and that the Cardinal was reasonable in his beliefs. The Cardinal struck a sympathetic figure as he pleaded his devotion to the Queen and that he only sought to serve her. But this was no ordinary court, it was a court of nobles in Paris, where Rohan was a great and wealthy family, where many had been at odds with the King and many more still resented the Queen. Add to that considerable sums were passed in bribery by the Duc of Orleans and other disaffected noblemen. The trial ended with the Cardinal acquitted of the charge of lese-majeste. Lamotte was found guilty as a thief and imprisoned. She was also publicly flogged, and branded. As she struggled against the branding iron, the poker slipped and impaled her breast. Lamotte hurled imprecations for all to hear: “It is the Queen who should be branded not me!”

The Uproar

The night of the verdict, against constable’s advice, Marie Antoinette attended a charitable benefit at the Paris Opera. When the verdict “Rohan Acquitted” was announced, the opera house erupted with applause. The crowds then whistled and hooted at the Queen, who left in dismay to weep at Versailles with her ladies in waiting. Repudiation of a French sovereign by court verdict and public rebuke had never before occurred. The Revolution had now begun. Within the year, Lamotte escaped to London. With her husband they enjoyed the money from the diamond necklace, now broken up, but she also took to the quill to spread malicious rumours about Marie Antoinette.

The Libels

Pamphlets by Lamotte of new stories of Antoinette’s sexual appetites and orgies at Versailles, and her claimed love letters between Rohan and the Queen became a new sensation in France as they were smuggled in by the thousands. The court literature against Marie Antoinette in the capital, by virtue of the necklace case, had now become commonplace throughout France. The economic position of the country worsened and King Louis, who drew closer to Marie in her sorrows, increasingly turned to her for advice in economic matters. The Queen’s increasing role and national disgrace weakened the position of Louis and the monarchy. Her presence galvanised and emboldened the opponents of the regime.

The Revolution

Revolution could have been averted in France after the necklace case, just as it could have been averted in America after the Boston Tea Party, but a course of action had been set in motion. The monarchy was humbled by the noblemen in court and people, all done with impunity. Going forward, the opponents of the regime, first among the nobles then later among the merchants and finally in the peasantry took heed and didn’t let up until the final violent overthrow of the French monarchy and the Terror among its citizens that followed. The nobles who sought to check Louis’s power and others like Phillipe Egalite who resented the King, came to be caught up themselves in the whirlwind of Revolution. That Revolution would claim the lives of thousands of nobleman including Phillipe, and end the privileges nobles had held in France. This was not what the nobles intended when they sought to vindicate Rohan and strike a blow against the King and Queen.

The Reversal

When Marie Antoinette learned of the necklace affair, she instinctively insisted on a public trial to avenge the offence to her honour and dignity. No one could have imagined how her act of hubris would trigger the catastrophic upheaval of Revolution in the 7 years that followed. In 1786, Madame Lamotte was imprisoned and branded; Rohan was acquitted at trial but forced from his Cardinal post to a remote posting. Marie Antoinette sat on her throne, still the glamorous powerful Queen of France, meeting out punishment to those who dared transgress her honour. In 7 years time, the Revolution would reverse the positions of the three players in this story. In 1793, Lamotte who had escaped her prison lived in comfort in England. The fortune she and her husband shared from the necklace was enhanced by the amounts made from the sales in France of her best-selling pamphlets against the Queen. Lamotte had become a hero of the Revolution. In 1793, Rohan too was living in comfort in exile. In the early years of Revolution, he returned in triumph and was elected to the Assembly. But Rohan saw the violent turn of revolution against the nobility and clergy including his family. Rohan escaped France to live out his life in a comfortable exile.

The World Upside Down

In the ultimate role reversal, the hunter became the prey. 1793 saw the final destruction of Marie Antoinette – humbled, humiliated and finally beheaded by her own subjects. The years of Revolution took everything away from Marie – her palaces, her jewels, her servants, her fine clothes, her friends and her family. Gone was her beauty and finery in which she took such pride and all the other trappings of her once fabulous life. In the end, Marie Antoinette was alone. She was taken from her prison cell, as a poor broken widow in her rags, old before her time. Now, it was SHE who would be the prisoner in the dock. SHE would have to answer the charges of the revolutionary tribunal, including the necklace case allegations of Madame Lamotte.

The Queen Beheaded

These charges still rang in her ears in the jeers of the crowd as Marie Antoinette road to her date with Madame Guillotine. The former Queen now rode in an open cart, her hands tied behind her back, and held in tether like a chained dog. Lamotte must have relished the irony that 7 years after she was flogged, branded and humiliated, 7 years after Lamotte swore vengeance, it was the turn of her tormentor to face punishment – Marie Antoinette was beheaded at age 37, her fair head held high for the populace to cheer her death. Such was the pendulum swing of great French Revolution, first set in motion by the case of the Queen’s necklace.

ray n

I’ve only very recently took on a very keen interest on the life and times of Marie-Antoinette. It all started after I watched Sofia’s work. Now, before the e-vultures come and attack my attribution, I initially thought Sofia’s production was lame. I “attempted” to watch her movie back in ’07, but couldn’t fathom the music with the period piece. After about 30 minutes or so, I turned it off.

5 years later(i.e last night), oddly enough, out of the blue I decided to give that movie another go. This time the movie went 120 minutes, and I was completely captured by it. In fact, I’ve seen it THREE times – in a row. The movie was her interpretation of the novel by Fraser.

Perplexed by everything, I started reading all materials surrounding the story/setting/piece/historical accounts/accuracy/fact & fiction.

Most articles I’ve come across attributed the sacking of the Bastille & the Women’s March as the primary turning points of the Revolution.

The story about the diamond necklace was something I did not knew about, until I stumbled upon this website.

I think the author has made a very valid argument about how the diamond necklace was the real catalyst behind the revolution.

I now wish to visit the Versailles ! No, I’m not a royalist supporter, nor am I a buorgeoise by any stretch of imagination. In fact, I consider Ernesto Guevara to be a true people’s hero (with some needed captions to clarify his life’s later decisions…)

With all that said, and what I’ve read so far about Marie-Antoinette, I am sympathetic for her.

Today’s corporate world can learn a lot from the events that lead to the French revolution.

Keep up the good work. Any web forum will attract the usual defractors and nay-sayers, but to keep a website running for 10 years is dedication. Just wanted to acknowledge that.

Cheers!

~r

Rusty Shackleford

hey how do you cite this website?

dauphiine

Your blog is amazing! Where did you find a picture of infamous necklace in color.

Kayla

Thank you for this it helped with my paper also and now I know more

Kristina

What I think people should understand, and this site obviously means to do, is give insight into a time period that is greatly debated about. History isn’t about dates and events. It’s about how a single human emotion can shape not only that person’s life, or the people around them, it can change an entire nation. It can lead to a debate hundreds of years later.

I beg, all of you, to understand that anger, frustration, ignorance, selfishness, fear, and above all else hope can trigger so much. Marie Antoinette was ruled by emotions. In her position, especially given the era she lived in, could show that. The only way to keep herself from exploding was to ignore those feelings. The feeling of useless at not being able to consummate her marriage, not to mention conceiving a child who is the be heir of France. The feeling of shame and disappointment at those same things. Women, especially royal women, were raised with the single purpose of being a figure head that pops out a male heir so as to secure a tie to the crown. She wasn’t able to do that. The only way to deal with those emotions, was to find someway to ignore them. If that meant spending vast amounts of money or having multiple love affairs… then so be it. She was a human being. She was a person, not a robot. In that day and age, she did what she had to keep herself from going crazy. Though she had a taste for opulence, in her later years, after the marriage had been consummated, and a male heir produced, she toned down her spending, and tried her best to fix the mistakes she had made. She was dealt a horrible hand. Her purpose in life was to be the cause of the French Revolution.

From the day that she was born, it was destined to happen. She was a woman born and bred for the day she got beheaded. Her elegance, grace, and poise carried her through. So she possibly shit herself on the way to be beheaded… wouldn’t you? She was only human.

Her impact on the world can be viewed as both positive and negative. The point is that, while she was alive, she made a statement. She changed a nation. No matter how unknowingly, she did it. What have you done? You’ve written comments on a blog about how silly she was. Congratulations. Maybe you should take some of that negative energy, and try to change the world. For better or for worse, do something.

If someone is talking about you in 200 years, I’ll apologize, but chances are, they won’t be.

Good or bad, Marie Antoinette made an impact, not only on her country, but people around the world, and to this day, she is still being talked about. So consider this when you want to bitch about a monarch… have you changed to world?

Karen

I have become fascinated with Marie Antoinette and all things attached to her.I have just finished reading the history text book by Antonia Fraser.I have learned so much about her story.Very tragic story. I am saving to travel to France and visit all things Marie Antoinette.Beside Versailles and The Petit Trianon does anyone have any suggestions where else to visit.I love this website and find it so informative.It is in my favourites. Thank you to the author.To all the people on here bitching about grammar and spelling, TAKE A CHILL PILL AND RELAX!

j.g

thank giddy god you were here to help with my paper, only place on the internet that doesn’t just cover the story but tell you the significance and what it did to the reputations of the royals, so well written. 10/10

Lucy

Kristina, I think this is a very immature comment to have made. First of all you say that history isn’t all about dates and events. No, I agree with that. But surely you will accept that the dates and events that are used should at least be correct? I also agree with you that we have to look at Marie Antoinette for who she was: a human being. I can understand that, under her circumstances she can perhaps be partly absolved of blame for her actions. However, when you ask, “have you changed the world?” perhaps you need to think about what you’re saying. Marie-Antoinette was born into privilege and purely through her status and the fact that she married a French Dauphin meant that she was always going to be featuring in history books. Now, the fact that she had absolutely no awareness of reality outside her sheltered palace walls and her disgusting extravagance while the people of France were living in poverty simply cannot be praised. Yes, she changed the world, but very, very easily for someone in that situation. In fact, any Queen of France could find it easy to change the world for better or for worse. If any one of the people commenting here had the opportunity she had in being Queen of France, we probably could have mucked it up just as well as she did and changed the world in just the same way that she did. If all it took to change the world was to be utterly incompetent in a position of power, then I think many of us could find it extremely easy indeed.

Kenda

i love Marie Antoinette,shes interesting to learn about.

Bailey

Thankyou so much! I have a huge essay due on this topic and this is extremely accurate and helpful! Now I have to find out how to turn this into a 6 page research paper by Monday. Ahh the joys of being in IB.

Vincent Stoppia

Wonderful synopsis of the Diamond Necklace affair, Bravo!

I have a question regarding the trial. When I read Frances Mossiker’s book, Recommendation Five states among other punishments that le Comte de La Motte is to be branded with G.A.L on his shoulder. Are you aware of the meaning of this mark; I cannot find a reference to it anywhere.

Sincerely,

Vincent Stoppia